The Ghost in the Glossy: Vogue’s AI Model and the Crisis of Realness

The Model That Wasn’t

AI model for Guess ad in Vogue August 2025 issue, BBC News

In the August 2025 issue of Vogue, a new campaign from Guess quietly appeared. The image was striking: a flawless model in a sun-washed denim jacket, platinum hair cascading over sculpted shoulders. But a closer look—specifically, a discreet footnote—revealed the twist: the model wasn’t real. She had been created by the AI company Seraphinne Vallora, founded by former architecture students Valentina Gonzalez and Andreea Petrescu.

The backlash was immediate. One Twitter user wrote: “That's disturbing. This is the direction AI should not be going in... wow,” (The Independent, 2025). Another wrote: “Had to end the Vogue magazine subscription I’ve had for years because the latest magazine used AI models ??? In Vogue? AI models in Vogue?” (The Independent, 2025). And that’t just it. Many weren’t just reacting to the use of AI—they were responding to something deeper. A sense of betrayal, perhaps. A glossy deception in a space where beauty is supposed to mean something.

To be clear: this article isn’t an argument against the use of artificial intelligence. AI is already shaping everything from textiles to trend forecasting, and it holds enormous potential as a creative tool. But when Vogue, a publication long synonymous with fashion’s visual language, features a digitally generated face with no story, no identity, and no authorship—readers are right to ask what, exactly, is being said.

Because in fashion, images aren’t neutral. They don’t just show; they communicate. And this one communicated something cold, uncanny, and strangely hollow. It evoked beauty, but not presence. Perfection, but not meaning.

The problem wasn’t the tech. It was the timing, the tone, and the absence of context. In a world already grappling with authenticity, erasure, and visibility, the image landed not as a revelation—but as a misread.

Virtual Isn’t the Problem — It’s the Point

Lil Miquela, WIRED

The backlash to Vogue’s AI-generated model wasn’t, at its core, about the unreality of the image. Fashion has always embraced artifice. It’s no stranger to fantasy, illusion, or aspiration. In fact, digital figures have already become part of the fashion ecosystem: Lil Miquela graced the front row years ago (Fashionista, 2018); Shudu, the so-called “world’s first digital supermodel,” fronted campaigns for Balmain (Dazed, 2018); and Noonoouri, with her wide-eyed proportions and surreal aura, even signed a record deal in 2023 (Forbes, 2023).

These figures, however, were never presented as anything but constructed. Their creators were known. Their identities were deliberately performative, even theatrical. Even their physical appearances make it obvious that they’re not real people; they look like dolls. And that’s because they weren’t trying to pass as real—they were designed to provoke, to play, to push aesthetic boundaries with full transparency. CodeMiko, a Twitch-based digital personality, even built her brand on the visible interplay between the real and the rendered.

In contrast, the Vogue x Guess AI model wasn’t a character. She had no name, no backstory, no arc. She wasn’t created to perform identity—she was designed to look like “beauty.” And in doing so, she sidestepped the question of who that beauty belonged to, or what it meant.

That distinction matters. The issue wasn’t that the model was fake. It was that she was presented without narrative, context, or point of view. She wasn’t a commentary on fashion—she was the fashion. A stand-in for the ideal, with no acknowledgement that the ideal itself is socially constructed.

As The Guardian observed in its early coverage of Shudu, the digital model raised ethical questions precisely because her image—though fictional—drew on recognisable visual codes. But there was never an attempt to obscure her origin. The audience knew what they were looking at. With Vogue, the ambiguity felt pointed. A footnote isn’t the same as a framing.

In the end, the outrage didn’t stem from disbelief—it stemmed from disconnection. People weren’t reacting to the fact that the image was generated. They were reacting to the fact that it said nothing. No statement, no spirit, no perspective. Just another face, eerily perfect and entirely forgettable.

AI Isn’t the Villain — Repetition Is

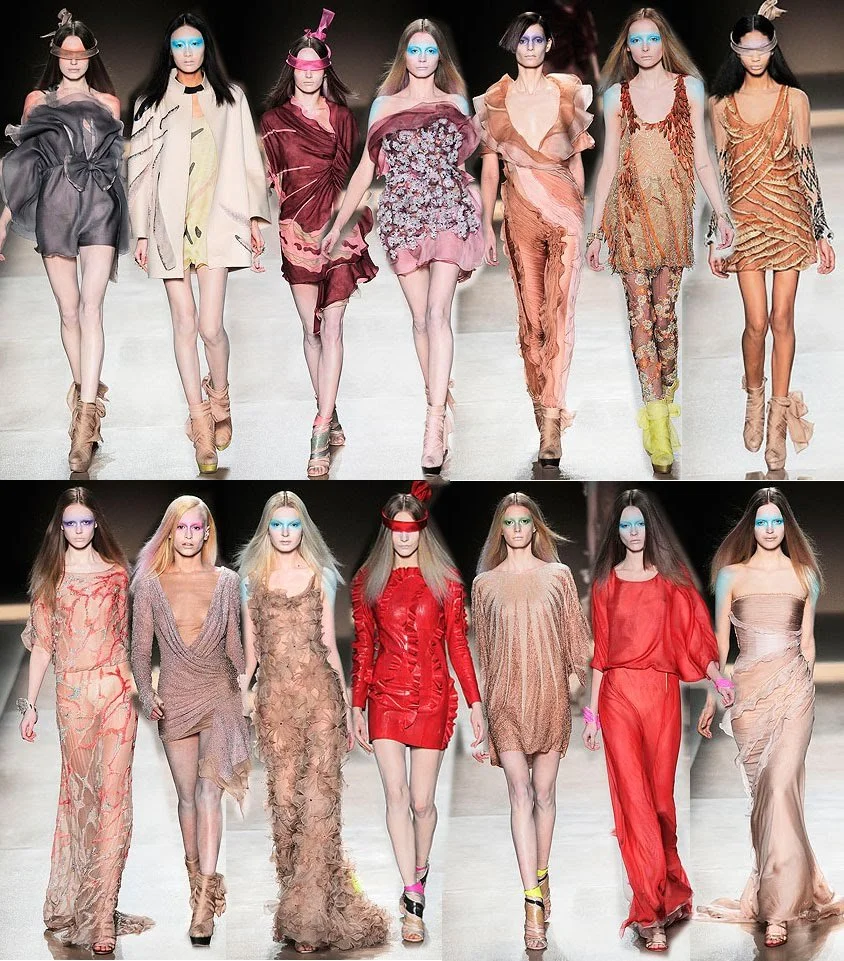

Valentino Spring Haute Couture Show 2010, Cool Chic Style Fashion

It’s tempting to blame artificial intelligence for what went wrong in Vogue’s August campaign — but that would be too easy. The technology itself isn’t the problem. The issue lies in how it was used, and more pointedly, what it was used to recreate.

Fashion, at its core, is about reinvention. It’s meant to challenge, to refresh, to move. But this image — an eerily symmetrical woman with Eurocentric features, poreless skin, and no visible flaws — felt like a throwback, not a breakthrough. Instead of imagining new forms of beauty, it reasserted the old ones, just rendered more perfectly. Or perhaps more precisely: more predictably.

AI is a tool. It can do extraordinary things in the hands of designers and creators with vision. It can be surreal, political, strange, radical. It can reflect culture back to us in ways that feel generative, not extractive. But in this case, the tool wasn’t used to dream — it was used to duplicate. What critics saw wasn’t innovation, but mimicry: the same impossible ideals, only more digitally polished.

That’s why the term “artificial diversity” caught on so quickly. The AI model had vaguely ambiguous features — enough to gesture toward inclusivity, not enough to challenge any norms. The result was something that felt manufactured not just in process, but in message. A composite beauty that promised universality, but delivered flattening sameness.

And perhaps that’s what people found so uncanny: not the image itself, but the implication that this is what progress looks like. A version of the future that’s been run through the algorithms of the past.

To be clear, this isn’t an argument for perfectionism in AI ethics, nor is it a call to retreat from experimentation. It’s simply a reminder that tools reflect the values of those who wield them. If you feed an AI centuries of Eurocentric beauty ideals, it will spit out perfection — but perfection as it’s always been defined. That’s not disruption. That's the default.

The real risk here isn’t the technology. It’s that we use it to repeat ourselves — more cleanly, more efficiently, and with far less imagination.

Who Gets Erased When Beauty Gets Automated?

Creatives behind Vogue World, Vogue

It’s easy to get distracted by the surface. The sleek polish of AI-generated models. The precision of their poses. The subtle cues of “believability” — just enough freckles, the shadow of a scar, pores algorithmically placed to suggest humanity. But beneath all that surface lies something deeper, and far more consequential: absence.

Behind every fashion image, there is a collaborative chain of labour. Hair stylists. Makeup artists. Nail technicians. Assistants. Lighting specialists. Photographers. Retouchers. Models. Runners. Editors. Together, they don’t just capture a moment — they build it. When an image is rendered by an algorithm, that entire network of expertise is collapsed into code. The result may look like fashion, but the labour behind it has vanished. And more often than not, so have the people who most need to be seen.

That disappearance isn’t accidental — and it isn’t harmless.

The fashion industry has long relied on precarious labour. The most replaceable roles — the freelancers, the junior stylists, the gig photographers, the background models — are disproportionately filled by women, people of colour, queer creatives, immigrants. These are the very people who’ve spent decades pushing for visibility in an industry that only recently began to diversify its talent pools. AI now threatens to undo some of that progress, not by reversing it outright, but by rendering it irrelevant.

Even the most realistic virtual model can’t replace what a real human brings to the frame. A digital face can’t negotiate for fair pay. It won’t speak up about creative credit. It won’t evolve its aesthetic, reference a cultural mood, or bring personal history to a pose. It can’t represent anything beyond the data that built it.

And here lies the ethical fault line: when beauty is automated, it becomes static. Safe. Controlled. The AI image doesn’t speak, challenge, age, make mistakes, or make statements. It performs without context. That may be efficient for advertisers — but it’s antithetical to fashion, an industry that claims to trade in self-expression and personal voice.

This isn't a new problem, but it’s a newly high-stakes one. Garment workers — often underpaid women of colour in the Global South — have long borne the brunt of automation and outsourcing. Now, the threat is encroaching upon the symbolic and creative tiers of fashion: the very roles that once seemed immune because they involved taste, vision, style.

And that’s what makes this moment so pivotal. The encroachment of AI into fashion’s symbolic economy should spark questions beyond aesthetics. Who is making this image? Who is benefiting from it? Who is no longer being called to set, or credited in the byline, or paid for their time?

Fashion has always relied on invisibility — of labour, of cost, of effort. But this is a different kind of erasure: not just of bodies, but of authorship. Not just of jobs, but of meaning.

If fashion wants to stay relevant, it has to make a choice: use AI to amplify the human, or use it to erase them.

Because a rendered face may be flawless — but it will never show up with lived experience, bold perspective, or a soul.

Realness Isn’t Just Aesthetic — It’s Emotional

Linda Evangelista British Vogue cover, British Vogue

Alek Wek Vogue Brasil cover, The Fashion Spot

In fashion, presence is everything. Not merely the act of showing up on a runway or in a photoshoot, but the deeper, almost magnetic way certain individuals hold space—transforming garments into statements, images into stories. Real models don’t just wear clothes; they imbue them with context, emotion, and history. They bring pulse and dimension.

Consider icons like Linda Evangelista and Alek Wek. Linda Evangelista’s legendary status arose not just from her striking beauty or chameleon-like ability to morph her look, but from a forceful personality and advocacy—standing alongside Naomi Campbell during times of entrenched racial bias in the 80s and 90s. Alek Wek, with her dark skin, short hair, and strong features, didn’t simply defy Eurocentric beauty norms—she reshaped them. Her presence was a bold assertion that beauty is multifaceted, a beacon of inclusivity that resonated beyond fashion’s surface. Each shaped the meaning of fashion, not only by their looks but by their very selves—their stories, struggles, and identities. Their impact was cultural, political, and profoundly emotional. They brought narratives that readers could feel. Narratives that the AI model would never be able to bring.

AI can replicate features. It can model symmetry, simulate skin texture, even generate what we might call “expression.” But it can’t carry identity. It doesn’t come with memory, conviction, or point of view. And it certainly doesn’t know how to inhabit contradiction — the kind that makes real people compelling.

What Vogue presented was not a new face, but a hollow one. The model seemed beautiful in a generic, frictionless way — engineered to appeal but devoid of surprise. It was, as many users put it online, “creepy,” “empty,” or “too perfect to be interesting.” Not because it was fake, but because it pretended to be real without earning it.

There’s a reason readers reacted so viscerally: they felt emotionally duped. A fashion image doesn’t just offer visual aspiration — it offers intimacy. That intimacy depends on a traceable sense of self. A who. A why. A voice.

Without that, all you’re left with is surface. And surface alone doesn’t move people — not anymore. In an age where audiences crave authenticity, story, and connection, a model with nothing behind the eyes feels less like the future, and more like an uncanny echo of a past we thought we’d outgrown.

Was the Outrage the Goal All Along?

Valentino Spring/Summer Show Paris Fashion Week 2016, Grazia

By mid-2025, the question almost asks itself: was this a blunder — or a calculated move? When Vogue published its August issue featuring an AI-generated model inside it, the image arrived without context. No profile, no backstory, no stylist’s notes, no creative director’s statement. Just a quiet footnote acknowledging that the face was synthetic. In an industry where presentation is everything, that silence was deafening. Readers were left not only wondering what they were looking at, but why it had been made at all.

And in the hyper-accelerated attention economy, could that confusion have been part of the design? We live in an era where attention is an extremely rare currency, thanks to the average person’s attention span. And its value is inflated by that scarcity. As I noted in my analysis of American Eagle’s controversial Sydney Sweeney campaign, brands are not merely competing to sell — they are competing to exist inside the cultural conversation. Outrage, inconveniently, remains one of the fastest ways to get there.

This tactic is hardly new. Fashion has a long history of courting controversy, from the Calvin Klein ad with Brooke Shields in 1980 to the deliberate offensiveness of Benetton’s 1990s ad campaigns. Valentino’s deliberate use of mainly white models for an Africa-themed show during Paris Fashion Week in 2016 is another good example. The difference now is the algorithmic feedback loop: provocation is instantly measured, rewarded, and amplified. A polarising image that draws fury also drives clicks, shares, and search traffic — all of which can translate into “heat” in brand-speak, even if it’s mixed with criticism.

The designers of AI models have been candid about user behaviour: people tend to engage more with perfection. Symmetry, flawlessness, impossibly smooth skin — the algorithm’s composite of what beauty “should” look like — commands likes and reposts. It’s not inconceivable that Vogue’s image was crafted to trigger precisely the unease it did: familiar enough to be aspirational, alien enough to feel uncanny. A visual that could not only showcase the capabilities of AI but also ignite a wider debate about its role in fashion.

But provocation is a volatile currency. Push too far, or repeat the tactic too often, and the effect flips. Audiences start to recognise the manipulation, and what once felt daring becomes transparent — even cynical. The outrage ceases to be thrilling; it begins to taste like bait.

Vogue may have already crossed that line. The AI model didn’t just generate buzz; it generated loss. Readers cancelled subscriptions. Comment sections overflowed with disillusionment. The brand’s credibility — especially among younger, more digitally literate readers — was called into question. This wasn’t just bad PR. It was a moment of reputational slippage, where relevance cracked under the weight of perceived insincerity.

Because here’s the truth: attention still matters. But so does perception. And right now, audiences are asking harder questions — not just what am I seeing, but why am I being shown this? If brands don’t have real answers, or worse, if they’re banking on the question being the entire point, they may find the next wave of attention looks a lot more like apathy.

Futureproof Fashion Isn’t Just About Tech — It’s About Truth

Technology in fashion, Forbes

I’ll say it again: this isn’t a manifesto against AI in fashion. Technology has always been part of the industry’s evolution — from jacquard looms to CGI runways. The issue isn’t the tool. It’s how we use it.

When AI is applied with intention — to push creative boundaries, to explore impossible concepts, to visualise ideas that words can’t contain — it can be exhilarating. Some of the most compelling fashion imagery in recent years has been AI-assisted. But when it’s used to mimic humanity without meaning, something vital is lost. Not just credibility, but connection.

What the Vogue backlash revealed isn’t fear of the future — it’s fatigue with surface-level storytelling. Readers weren’t rejecting innovation; they were rejecting a version of progress that felt hollow. An image that said “this is beauty,” but couldn’t tell you why. A face that looked perfect, but didn’t know what it was saying.

The real question isn’t whether fashion should use AI — of course it will. The question is: what story are we telling when we do? Are we using this technology to deepen the conversation, or to avoid it altogether?

To futureproof fashion, we need more than new tech. We need the truth. We need authorship, perspective, emotion — the very things that made fashion matter in the first place. AI can assist, enhance, even inspire. But it can’t substitute soul. And when we try to make it do so, the audience notices.

Because they’re not just looking. They’re listening.